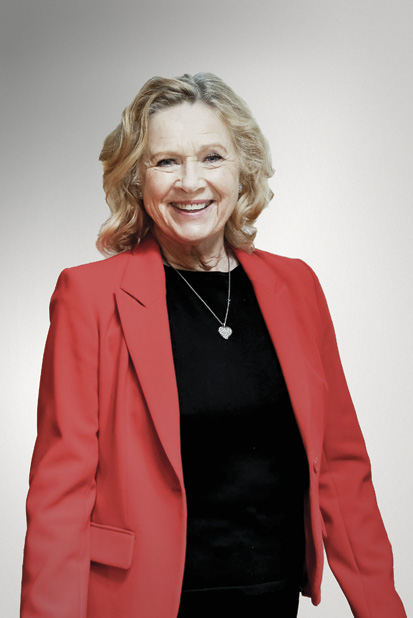

Liv Ullmann Living and loving

Actress, author, director, muse. During a career spanning 60 years, Liv Ullmann has been all of these things. What may surprise many is that the star who made her name with raw, soul-searching performances always wanted to be a comedian. Scan Magazine caught up with the Norwegian icon at London’s British Film Institute, where she was opening a season dedicated to her long-time collaborator, Ingmar Bergman.

Liv Ullmann sparkles. When she talks, she has a way of inviting you in – encouraging questions with a friendly tap on the arm and answering with a directness that would be surprising in Hollywood. Here in London, though, it feels as natural as if an old friend has just come to visit. “I am here in the UK so often,” she says. “When Ingmar was alive, he would always say that he was coming and then get sick at the last minute and send me! But 50 years after he went to Fårö to build his house – 50 years after he became an islander – he will now appear all over the world. Yes, Ingmar may have left us, but he is still very much alive.”

Ullmann worked with the great auteur on ten films. They eventually had a child together – Linn Ullmann – and long after their affair ended, they remained “painfully connected”. As Bergman lay dying, Ullmann recalls how she felt compelled to visit. For the first time in her life, she chartered a plane and found him “already on his way”. She sat and held his hand, and told him just one thing. “I said to him that ‘I came because you called. I came because you called, as you called so many’.”

It is a testament to the duo’s life-long friendship that, years after his death, Ullmann’s voice still catches as she remembers their first collaboration on Persona. It remains one of her happiest film memories. “A wonderful role, even though I thought I was too young for it,” she says. “I was performing with Bibi Andersson, who is my best friend, and I fell in love with Ingmar, and he fell in love with me. And for a while, we lived together in the house that he built, exactly where he dreamt he would, on his island, Fårö.”

That home is now a museum, and you can still see the scribbles on Bergman’s study door where the lovers would write notes to each other about what sort of day they had had. “A heart if it was good, a cross if it was sad,” Ullman recalls. After she left, Bergman would repaint all those little notes to stop them being beached-out by the sun. “Now,” Ullmann says, sadly, “nobody is writing on that door, so soon they will all be gone.”

A fateful meeting

Ullmann first met Bergman when she was visiting Bibi Andersson in Stockholm. By then, she was an established actress. Bergman had even seen some of her films. The rest, as they say, is history. But what was it that inspired her to consider a career in the spotlight in the first place?

“When I was very young,” she says, “I made up stories and performed them when my mother had guests… and for once, I had their attention!” She adds that, while she always had a knack for making people cry, “I honestly really wanted to be a comedian, and in school, I would write small comedies and people really did think I was funny.”

It is true. Ullmann’s talk is peppered with comic asides, which she relates with a warm, self-deprecating humour. In fact, it was the desire to work on a comedy that made Ullman turn down Fanny and Alexander, which Bergman had written especially for her. For a whole year after, Bergman refused to speak to her, writing letters addressed simply to ‘Dear Ms Ullmann’.

After leaving school, Ullmann went to London to study drama. “I lied a lot!” she admits. “I told everyone I was 19 and had just finished my student exams, and was engaged – because I wanted to be like all the other girls. They all knew that I’d lied, but I didn’t know they knew!”

Back in Norway, a botched audition lead to the offer of the lead in Anne Frank in a small theatre in Stavanger. “You can’t miss that, if you have a heart.” Film offers and that fateful meeting with Bergman followed, but while the director’s work is often described as dour and serious, what Ullmann remembers is the fun. “He was a storyteller. He had such fun directing and we had fun with him. We were all so close – we were best friends,” she says.

Thanks, in no small part, to Bergman’s international reputation, Ullmann soon found herself being offered roles in Hollywood, something that did not quite go as planned. Ullmann: “People were saying, ‘She’s the new Ingrid Bergman, she’s the new Greta Garbo’, so I went and played the lead in Lost Horizon, though I really couldn’t dance or sing… and everyone was saying ‘Oh! You’re so wonderful’. Then I did 40 Carats and they were telling me that Elizabeth Taylor was crying because she couldn’t do the film. I was 30 years old, looked 25, and was supposed to be this 40-year-old sophisticated New Yorker. I spoke even less English then than I do now! But, to be honest, I loved it. I got to dance with Gene Kelly, and everybody was beautiful to me. I had a fantastic house, with a bathroom that kings could have held court in. But in one year, I did four films and did something that no one else had ever done before: I closed down two studios!”

Demons and disasters

Today, Ullmann is primarily remembered for her incredible body of film and TV work, but theatre has always been her first love. And, while America’s film studios may have wasted her talents, on Broadway she finally had her ‘Hollywood moment’ with award-winning runs in A Doll’s House, Ghosts, and Anna Christie.

Oddly, while Bergman had always been critical of actors who went abroad to work, he flew to New York to see her perform. It was, Ullmann feels, because it was something he would have loved to do himself if he had not been so shy. She goes on to relate the story of how Barbra Streisand invited Bergman to her Hollywood mansion to discuss a film – and told him to bring his swimming trunks. “He got straight on the plane and flew home!” she laughs.

Another collision with Hollywood royalty was equally disastrous. “Fear would fill him, but it did not hinder him,” Ullmann explains. “He found pockets of safety in the midst of what he called his demons. He found safety in creativity and believed that you always need others to create.” On set, he was an incredibly generous director, allowing the actors to find their own characters. His scripts were, how ever, sacrosanct. The only actor to ever break that rule was Ingrid Bergman. “While we were reading for Autumn Sonata, she would stop all the time and criticise the script. When the reading was over, everybody left and I was alone with him and he cried. He really cried.”

50 years on, and while Bergman may be gone, Ullmann feels that she will always carry a little of his essence with her. “Once you are with someone lovely, part of that loveliness will always be with you. Once you are with a genius, some of that will be with you. It’s contagious to be with good people, just as it is contagious to have leaders that are no good and spread hate.”

TEXT: PAULA HAMMOND

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email