Leading the charge: Scandinavia’s greatest inventions

By Lena Hunter

The blueprints of Google Maps as we know it were laid out by a pair of Danish brothers. Photo: Google

Today, Scandinavia is fertile ground for innovation. Its cosmopolitan cities champion a favourable work-life balance and generous welfare state, allowing for bold entrepreneurship and experimentation. In recent years, Sweden has been pegged as a haven for start-ups, home to the second-most unicorn companies per capita in the world. The focus is largely on fin-tech, but bootstrap companies of all orders are flooding to the Nordics to chase a billion-dollar valuation. With that in mind, let’s take a jaunt through Scandinavia’s innovative history and greatest inventions.

Google Maps is about as indispensable an app as you’ll find. But when Danish brothers Jens and Lars Rasmussen co-founded a digital mapping app called Expedition, in 2003, they were breaking new ground – and their work quickly caught Google’s attention. The tech giant promptly gobbled up the start-up, tweaked the software and launched Google Maps in 2005.

Another milestone in smart location technology was the STDMA data link. In brief, this 1980s breakthrough allowed the Global Positioning System (GPS) to send and receive location information every second – paving the way for accurate, real-time location reports. The inventor was Hakan Lans, a Swedish multi-engine plane pilot hobbyist, who immediately saw the STDMA data link’s potential in air-traffic management. Today, it has become integral to global flight-tracking systems.

Street art in Christiania, Copenhagen – thanks to a Norwegian invention. Photo: JRodSilva

The first ever unicorn

While Lans’ invention is a behind-the-curtain hero, we’re all familiar with Niklas Zennström’s. The Swede co-developed Skype – just as faster internet connections were becoming standard – punting expensive long-distance phone calls into obsolescence. Speaking to the company’s head-spinning early growth, Skype was the first ever unicorn company in the Nordics and sold to Microsoft for 8.5 billion dollars in 2011.

20 years before Skype ended the party for landline calls, Bluetooth ended the party for data cables – sort of. Bluetooth was developed by Swedish telecommunications company Ericsson, and named after Harald Blåtand, a Viking king who ruled Denmark and Norway (touché, Ericsson). Today, the technology allows us to wirelessly send and receive data via short-wavelength UHF radio waves.

Stockholm has the second-highest concentration of unicorn companies per capita in the world, after Silicon Valley. Photo: Susanne Walström, imagebank.sweden.se

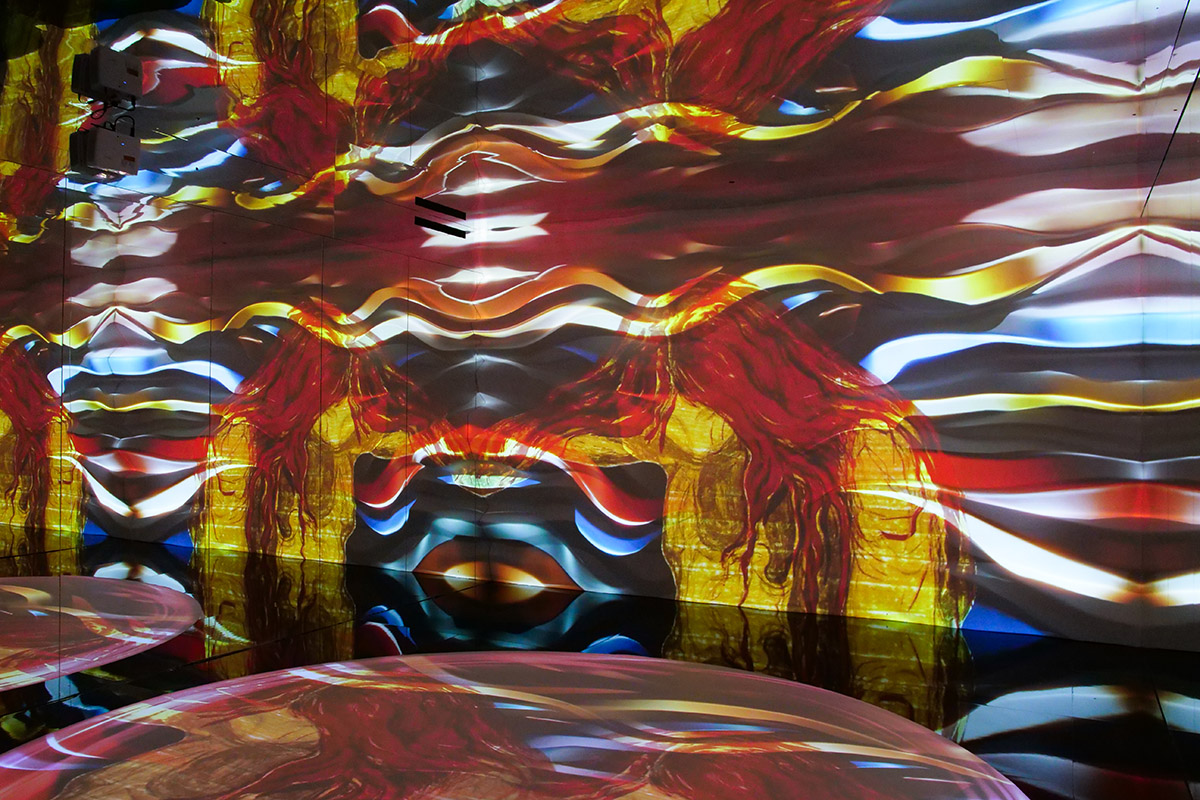

Speakers and screens

Best of all, Bluetooth allows us to play tunes via our portable loudspeakers. Incidentally, the loudspeaker has its roots in Danish research. In 1915, Peter L. Jensen pioneered the field when he was the first to manufacture moving-coil loudspeakers. Though Edward W. Kellogg and Chester W. Rice are considered the inventors of those widely used today, Jensen’s visionary contribution, over 100 years ago, to our ability to turn it up should not be overlooked.

We take for granted the ever-thinner, lighter, brighter and more responsive screens that surround us. But they are only possible thanks to the discovery of ferroelectric liquid crystals by the Swede Sven Thorbjörn Lagervall in 1979. In the ‘80s, Canon, Seiko, Sharp and Mitsubishi were amongst the major companies to pounce on the discovery in the race to channel it into display-technology perfection. The upshot was the modern Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal Display (FLCD) as we know it – and which we are helplessly glued to.

Loudspeakers, and the Bluetooth technology that they make use of are Scandinavian inventions Photo: Bang & Olufsen

Pacemakers and explosives

In the sphere of health, Sweden has also made major contributions. In 1958, Rune Elmqvist developed a battery-run artificial pacemaker – a device which generates electrical pulses to regulate the heartbeat. The first pacemaker operation was performed by surgeon Åke Senning at Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, and the medical breakthrough went on to help millions of people worldwide.

Arguably the biggest contribution by Sweden to science was in the 1860s, when Alfred Nobel invented dynamite and the blasting cap to ignite it. After being licensed for use in America, it paved the way for the Industrial Revolution, as it enabled mines to be dug deeper and faster, and paths to be cleared for the construction of roads and railway networks.

From one end of the explosives-spectrum to the other: safety matches were also developed in Scandinavia. Matches were nothing new – though the heads were made of phosphorus, which was unpredictable and often dangerous. It was Swedish Gustaf Erk Pasch who had the simple but brilliant idea to move the phosphorus onto the side of the match box, and to replace it with a non-toxic version in 1844. The innovation blew up – figuratively – and saw Sweden charge to the top of the match-production leader board, making up to 75 per cent of the world’s total stock of matches.

At times, Sweden has produced up to 75 per cent of the world’s matches. Photo: Peter Knutson

Norway, reporting for duty

50 years later, the Norwegian chemical engineer Erik Rotheim was granted a patent for the aerosol spray can. It was Oslo in 1927 and – despite the later proliferation of his invention – commercial applications for the technology at the time were not forthcoming. Rotheim died in 1938 and the following year his aerosol company went bankrupt. An American company bought the patent for 100,000 Norwegian kroner, and the 1940s saw an about turn for the invention. The decade witnessed the birth of the airbrush, aerosol paint, and aerosol bombs for insect control. Today, aerosol cans are everywhere. Rotheim may have died before he was appreciated, but the pioneer can rest easy knowing that he made it onto a commemorative stamp in Norway, in 1998.

But forget aerosol cans for the moment. Norway’s real gift to mankind is the cheese slicer. Semi-soft cheese of the type found in Scandinavia has a curious consistency that will not be tamed by a knife alone. It’s soft – but it needs to be manhandled. In 1925, the carpenter Thor Bjørklund saw this and – a practical man as he was – designed and patented a plane-like tool for slicing cheese – a design still sold today. Cheese has been around for well over 7,000 years. It’s almost unthinkable that we, as a species, made do for so long without a cheese-slicer.

Left: Thor Bjørklund’s invention could not have come sooner Photo: Arla. Right: Scandinavia’s favourable buisness and leisure conditions have made it a haven for start-ups and entrepreneurs. Photo: Ulf Grünbaum, Imagebank.sweden.se

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email