Erik Magnussen Design: Timeless design rooted in functionality

By Heidi Kokborg

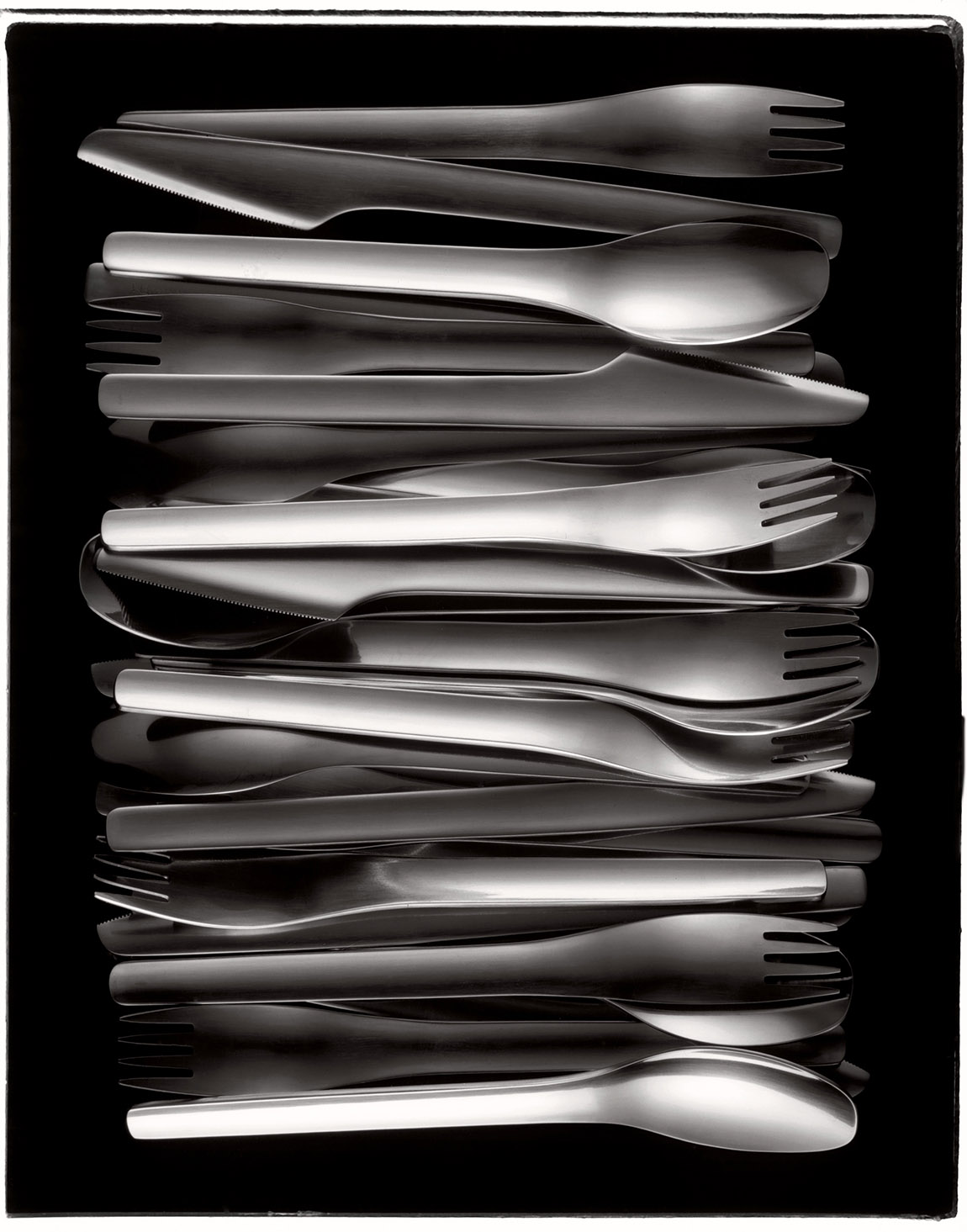

HANK tableware for Bing & Grøndahl (1970), widely used by DSB and private. Photo: Ture Andersen

Known for his iconic Stelton EM77 thermos jug and a relatively quiet, user-focused approach to design, Erik Magnussen created everyday objects that are still admired – and used – decades later. With a deep respect for function, form, and the users, his work continues to shape how we think about design today.

Erik Magnussen (1940-2014) never worked from a large studio. He did not have a team of assistants, nor did he aim to be in the spotlight. Instead, he worked largely solo; thinking, refining, and prototyping until the idea was resolved. “He wasn’t interested in fame. He preferred being at the factories, talking to the people who made his designs. That’s where he felt at home,” say Jonna and Magnus Magnussen, wife and son of Erik Magnussen.

Born into a creative family, Erik Magnussen was surrounded by both art and engineering. His grandfather was a respected art dealer, while his father was an engineer. It was a blend that would shape his career – technical rigour paired with artistic instinct.

EM77 for Stelton (1977). Photo: Ture Andersen

Design that makes sense

Erik Magnussen did not believe in creating products just for the sake of creating products. “He always asked: can this be justified? There needed to be a reason to add something new to the world. If a product didn’t improve what already existed, he simply wouldn’t make it. A chair had to offer more than another chair. A cup needed to solve a real problem,” says Magnus Magnussen.

Nameplate in fine porcelain. Ceramitag. Photo: Ture Andersen

His iconic Stelton thermos jug is a perfect example. Designed in the 1970s, it opens and closes automatically and has been updated over the years to reflect technical innovations. Its clean, graphic shape is instantly recognisable. “That is one of Erik’s trademarks. He made things look so obvious – as if it should be like that.”

Another standout is the HANK tableware series, created for use in public institutions like DSB (Danish State Railways). The mix of durable porcelain with plastic handles and colour-coded accessories not only communicated function but became a commercial success. Its graphic, modern feel appealed to public institutions and private users alike.

“He saw himself as an average consumer. He designed for people like himself, and believed that good design should be affordable, accessible, and able to last through generations,” explains Jonna Magnussen.

Chairik chair (1996), Montana Furniture. Photo: Montana Furniture

Ingenuity with a touch of artistry

Although Erik Magnussen was educated as a ceramist at the School of Applied Arts and Design, his creative path expanded rapidly. After his early work in ceramics, he worked with Torben Ørskov, one of Denmark’s most significant design merchants from the 1950s. This resulted in a series of furniture designs – including a chair held together without screws, where the fabric acted as a structural element. Later, he developed modular furniture systems in Malaysia that could be shipped flat-packed, assembled without tools, and transported efficiently.

“His ideas were often ahead of their time. He was a bit obsessed with solving problems – sometimes down to the shipping and storage. It wasn’t just about designing a beautiful chair. It was about designing a better chair, from start to finish.”

Many of Erik Magnussen’s designs were crafted through model-making rather than sketching and drawing. Ideas developed in his head before his hands got to work. He was known to build full prototypes himself – refining as he went, challenging every joint and connection. “There were rarely unnecessary details. Aesthetics emerged from smart thinking. Nothing was just decorative,” says Jonna Magnussen.

Tableware for Stelton (1995). Photo: Piotr&Co

A full-circle approach

Erik Magnussen’s design thinking was not limited to the product alone. He was involved in catalogues, graphics, exhibition stands, and packaging. He collaborated with skilled craftsmen and manufacturers, valuing their input as part of the creative process. “He didn’t want to just hand something off, but rather wanted to be a part of it from start to finish,” says Magnus Magnussen.

In that sense, his work somehow echoed the Gesamtkunstwerk tradition: not in its romanticism, but in its totality. Whether designing porcelain door signs that avoided glare in direct sunlight (a door sign that has just been relaunched) or a chair that could be assembled in six intuitive parts, his work was always intelligent, inventive, and user-driven.

Erik Magnussen also believed in tolerant design – objects that could fit naturally into many kinds of environments, across styles and incomes. “He did not see the point in designing for an elite. Design should be lived in. It should feel good to use, not just to look at,” add Jonna and Magnus Magnussen.

While some designers and artists chase trends, Erik Magnussen chased improvements. He was not interested in creating showrooms and galleries, but in making life better. Even today, many of his products are still in production and are used and appreciated daily by customers worldwide.

Four plastic parts held together by two steel tubes. Plasma for Thornet (1996). Photo: Piotr&Co

Web: www.erikmagnussen.com

Facebook: Erik Magnussen Design

Instagram: @erikmagnussendesign

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email