Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love Film Review

Tall, deep-voiced and irresistibly handsome: the enigma of Leonard Cohen has faded little since his death in 2016. He was the poet-turned-singer that made depression sexy. Walking in Montreal a year after he died, I was not surprised to find fresh flowers left outside his house. Cohen never abandoned his home city, though he did take long, uninterrupted spells abroad. In 1960, at the invitation of novelist George Johnston, Cohen moved to the Greek island of Hydra, hoping its atmosphere of drug-fuelled creativity would resurrect his experimental novel Beautiful Losers. Five months later, he used his grandmother’s inheritance to buy a small house with poor plumbing and intermittent electricity.

TEXT: ALEXANDER BRETT

Cohen was seldom without a muse. Not long after he arrived in Hydra, he met Marianne Ihlen, a 25-year-old Norwegian living on the island with her young son, Axel. Abandoned by her husband, Marianne was invited, along with her son, to move in with Cohen, and so blossomed a relationship that would last some six-and-a-half years. She became his muse and servant; he became a father to Axel. Their affection for one another was genuine, but Cohen’s womanising soon made it impractical. When he invited them to North America, Cohen confirmed what he already knew: the dull realities of family life did not suit him. The magic dissipated. Axel was so unhappy that he wrote his name across every wall in the house. Cohen and Marianne drifted slowly apart; keeping in contact but spending, as Cohen put it, at first two months together, then two weeks, then two days. At the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival, Cohen introduced the song he had written for her, So Long, Marianne, by asking, helplessly, whether she was in the crowd. “I hope she’s here, maybe she’s here…?”

This clip is one of the most powerful in Nick Broomfield’s latest documentary Marianne and Leonard: Words and Love, a film that greets you humming and leaves you sobbing. It is a biopic – taking us from Cohen’s privileged childhood to his unexpected musical career, through to his time at Mount Baldy Zen Center and the multi-million-dollar embezzlement that left him penniless – but it always keeps sight of the premise, remaining, throughout, a tale of confused but forgiving love. We learn much about Cohen’s characteristic shyness, as well as his previously undiscovered feminist sympathies, but most importantly, we hear Marianne’s voice, subtitled from the Norwegian, giving us undiluted insight into a fascinatingly complex relationship.

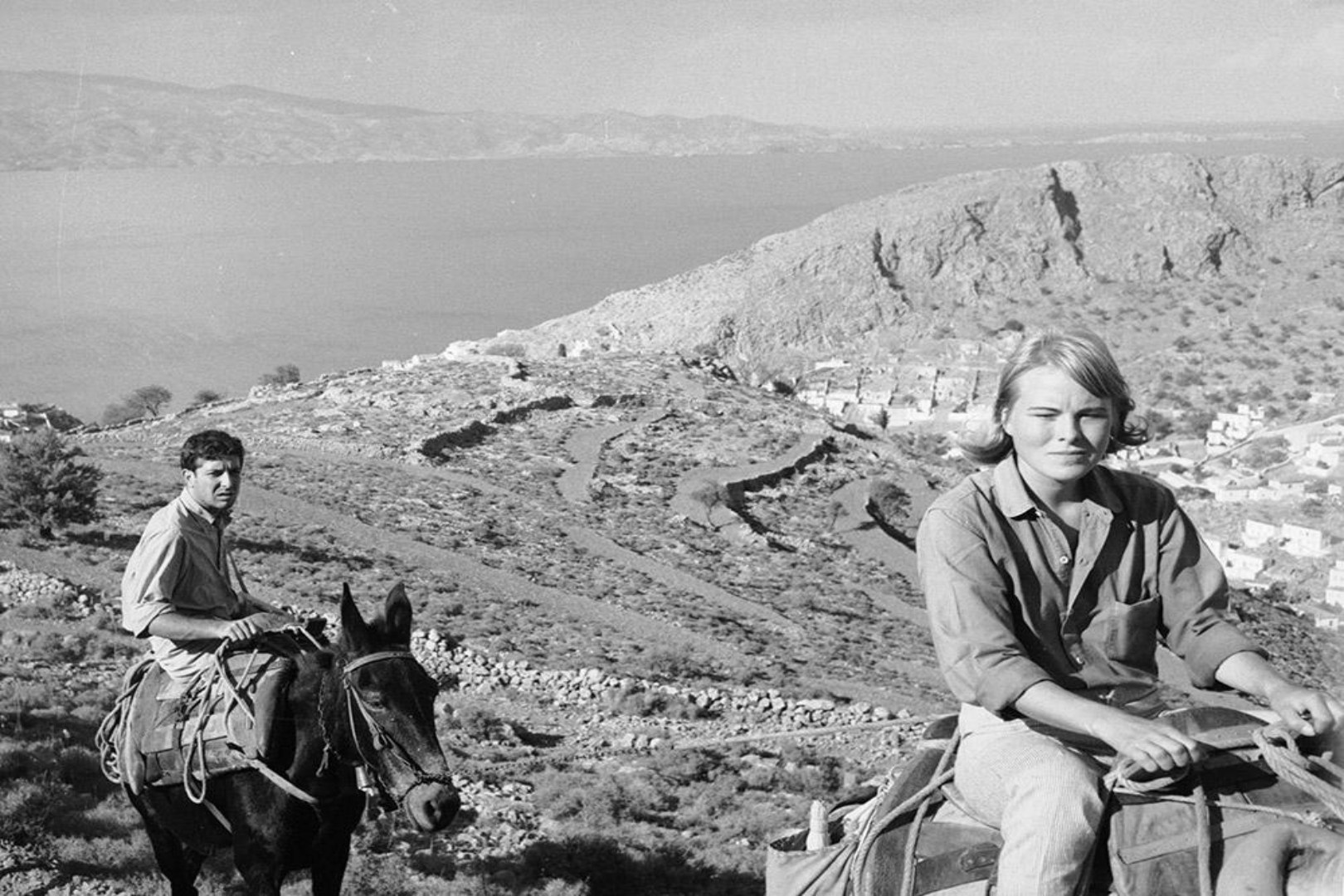

The direction is excellent, made all-the-more exciting given Broomfield’s personal connection to Marianne (he was her lover before – or perhaps alongside – Cohen). He is perfectly placed to describe Hydra – a bohemian colony where even the donkeys were on speed – and, to an extent, Cohen’s later life. Moreover, his perceptions are intriguing and (despite jumpy editing) he draws what he wants from his contributors. The final moments of the film are particularly impressive. We are shown Marianne, dying in hospital, being read aloud Leonard’s farewell letter, knowing he himself will die just three months later. Though Marianne remarried, the couple were never out of touch. The letter proves they were never out of love either. “You know that I’ve always loved you,” it reads. “Goodbye old friend, see you down the road.”

Alexander Brett is the editor of Fika Online, a blog dedicated to Nordic lifestyle, culture, travel and more.

Web: fika-online.com

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Scan Magazine Ltd.’

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email