The National Library of Finland: The home of Finnish values, identity and culture

Text: Anne-Koski Wood | Photos © Marko Oja & The National Library of Finland

Deep underneath Helsinki’s Senaatintori Square, carved into the solid rock, lies the archive of the National Library of Finland. The archive safeguards Finnish cultural heritage by storing printed and audiovisual materials, as well as collecting and preserving documents published on the internet. “The focus is on the future,” says Professor Kai Ekholm, the national librarian.

When Ekholm started his post as a national librarian at the National Library of Finland 17 years ago, he wanted to achieve a few goals: to renovate the 174-year-old building, digitise the Library collections and lower the admission threshold to visit the library. Now, retiring from his post, he has completed his objectives. During his time, the world has changed and the growing traffic on the internet has created new challenges. One could ask: what is the point of storing printed materials, when a lot of it is available online anyway? Ekholm reminds us that most researchers will almost always want to see the original pieces. Viewing an original item in real life is always an experience and might give an insight, which could be missed if only doing research on the internet. Ekholm does not see any competition between online archives and built archives. “We need them both.”

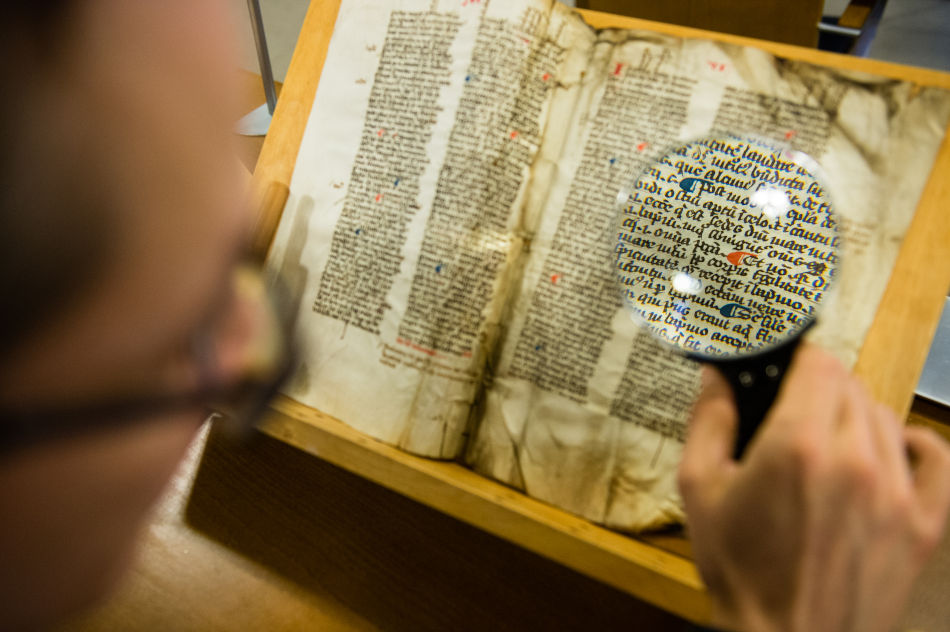

The rarest materials are available for study in the special collections reading room.

A book can change someone’s life

“Books have a form of responsibility,” Ekholm states. “That’s why it’s so crucial to write them well!” He is happy that currently, Finland has many young writers who have a lot to say, but wishes authors had more back up both financially and in general.

Ekholm is worried about screens taking over books. He calls the current age the ‘ephemeral era’: “Things on social media that are born in the morning, are dead by the evening. The aim of these different phenomena that appear on our screens is to block our memory and to keep us hooked, so that we can be sold more stuff we don’t need, while we are losing touch with cultural knowledge and inner truth. All that is left are some fragmented truths, from which we have to re-build our world.” The National Library, on the other hand, offers a point of connection, where culture is shared and moves from one generation to the next. “In the same way that nobody actually owns colours, no one owns culture either, but sharing it joins us as a nation. People want to be part of a culture.”

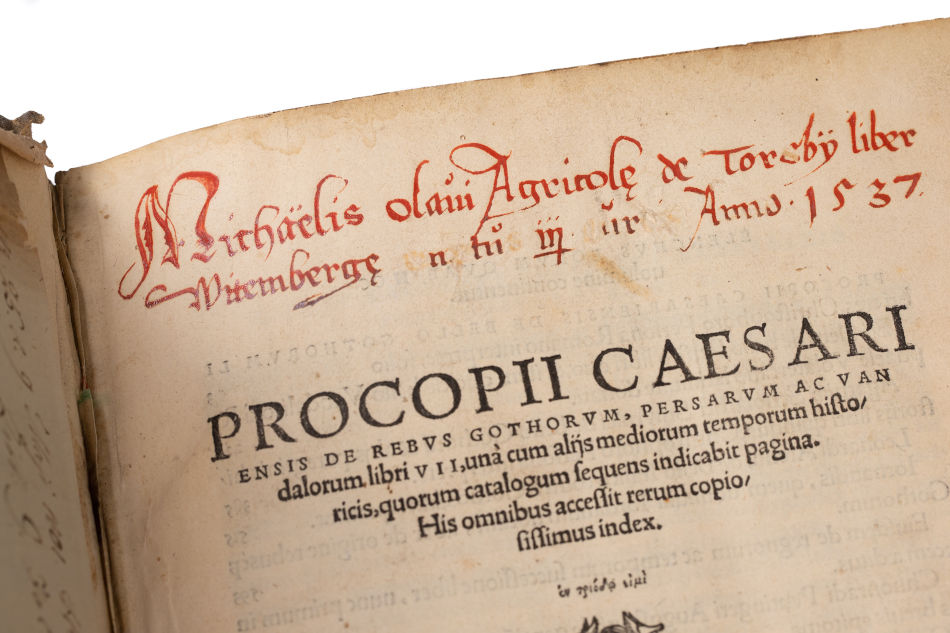

Treasures, such as a book that used to belong to the “father of Finnish literature”, Mikael Agricola, are for the most part acquired via donations.

The real treasure: private collectors

One vital aspect keeping the cultural heritage alive are the private collectors. These collectors have dedicated their lives to their passion by collecting rare books, maps, and special editions. Plus, their donations keep the national heritage alive and constantly evolving. Ekholm calls these gifts and donations ‘success stories’, and they have enhanced Ekholm’s career along the way. He gives the example of a collector who had finally found and purchased some manuscripts by Jean Sibelius at Sotheby’s. “The package arrived in July, but I had to wait for the right moment to open it. Finally, the time arrived a month later, when I could hand over a pair of scissors to the collector and ask her to open it. That moment, when Sibelius arrived home, has forever stuck in my memory.”

The extension for Engel’s building, Rotunda, was designed by Carl Gustaf Nyström in the early years of the 1900s. The Late Jugend architecture was influenced greatly by Nyström’s study trip to Vienna.

Web: kansalliskirjasto.fi

Facebook: Kansalliskirjasto

Twitter: @NatLibFi

Instagram: @natlibfi

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email