Dome Karukoski: A meeting with the saviour of Finnish cinema

By Paula Hammond | Photos: Marek Sabogal

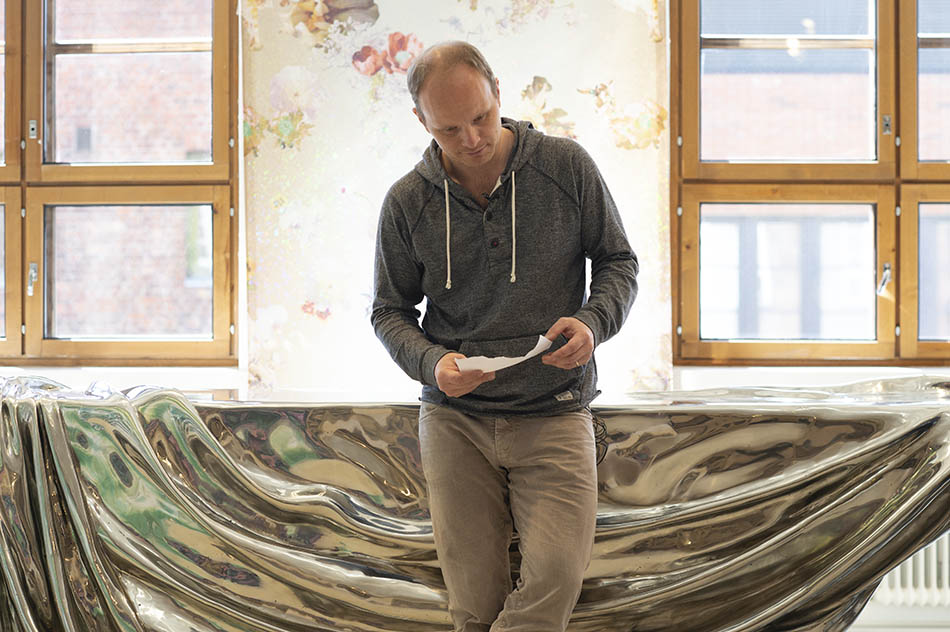

Dome Karukoski. Photo: Emine Lunden

Acclaimed as “the saviour of Finnish cinema”, Dome Karukoski is a rarity: a maker of art house films that attract blockbuster audiences. Scan Magazine caught up with the Finnish director in Glasgow where his latest film, The Grump, was charming film festival attendees.

“The idea that if we’re making an art house film, we have to make it as difficult as possible, or that if it’s a commercial film, we have to have to load it with ‘ha ha jokes,’ is just stupid,” Karukoski says. “The Grump was a super box office hit and the Number One film in Finland last year. But at the same time Glasgow will be its seventh film festival appearance. People are now calling it commercial but if it wouldn’t have become a box office hit, would that make it art house?!”

Talking to Dome Karukoski is like trying to catch lightening. He seems to be doing a dozen things at once: eating lunch, reading messages, checking the clock. He bounces from topic to topic, with an infectious enthusiasm and impish humour. “Actually, the way I’m living and travelling,” he laughs, “I can’t see me lasting much longer!”

Stills from The Grump

The father’s footsteps

Karukoski’s passion for film is, he admits, “a bit of a puzzle”. His father was an actor and in the way that young boys often idolise their fathers, he applied to acting school. “I didn’t get in, luckily,” he adds. Instead, Karukoski attended film school without direct knowledge of a directorial profession, but with a burning desire to be involved with films.

Film school turned out to be a vital time for the fledgling filmmaker. “I was raised by a single mom who didn’t have that much money so we didn’t have a camera. We couldn’t afford even the 8-millimeter cameras that all the directors usually shoot films with when they’re kids. So film school, which was government funded, allowed me to practice and rehearse the simple language of cinema,” Karukoski says. “To try different things and mould myself into the filmmaker I am.”

Embracing strong females

His debut feature, Beauty and the Bastard was the surprise festival hit that catapulted the then 28-year old into the big time. Since then Karukoski has made his name with human dramas, filled with passion and quiet, contemplative moments. His heroes are often traumatised social outcasts who, like the delinquent boys in The Home of the Dark Butterflies, struggle to find their place in the world. Although he feels that many of his stories are about men for men, his worldview is one that embraces strong independent women. “In Heart of a Lion and The Grump the mother characters are proud women who never stand in the shadow of their husbands, like my own mother. She’s a feisty woman,” the director laughs. “If she meets a bear in the forest, she’s going to kick its ass! So in a way for me it’s difficult to direct a more timid woman. I do feel that a lot of my female characters could have been more developed but many of them are very strong and feisty and I like that.”

A familiar inspiration

For The Grump, it was Dome’s poet-actor father who provided the inspiration. “My father was always complaining that there weren’t any stories about his generation but then I found this book by Tuomas Kyrö, which in Finnish translates roughly as The Man Whose Day is Always Ruined. My father was a grump and I’m starting to be one too! I’m usually a super positive fellow and when you look at pictures of my father when he was younger, he was always smiling. But I think the negativity comes from one thing: when you start having back problems. When I was 16, I would bounce out of bed. Now if I do that I have to go straight to physical therapy! So I’m entering the grump world.”

Dome Karukoski. Photo: Emine Lunden

A lesson learnt

Positive change is also a reoccurring theme of Karukoski’s heartfelt films and something that he thinks more and more about as he gets older. “I’m an optimist at heart,” he assures. “I think there’s always a choice. It’s easy to carry on down the same path but choosing change – like in Heart of a Lion, where the main character turns his back on his neo-Nazi friends – usually rewards you.”

It’s a lesson he’s learnt in his own life. Choosing film school and not moving to the US with his American father were, he says, life-defining moments. “It sounds like a cliché but the important thing is to stay true to yourself. I could have made a lot of money just by accepting work because someone needed a director but I always think that every film I do might be my last so it has to be something I’m proud of. The stories have to have something human in their essence. Something profound.”

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email